I have a soft spot for terrible taxidermy. It’s so earnest; it offers itself so humbly to us even when we know, and it knows, that it resembles no animal that has ever walked this earth. But I have done my best, the absent taxidermist seems to plead with every rough stitch on the animal’s side, through the cloudy gaze of its lopsided glass eyes. I have tried to show you a shark.

The best places to find terrible taxidermy are old or underfunded museums; Berlin’s Naturkundemuseum, for instance, houses the preserved form of Alexander von Humboldt’s loyal parrot, who accompanied him through the jungles of South America and whose stuffed form enjoyed a gregarious afterlife in Berlin, only to be torn nearly in two in a bombing raid in the Second World War. Half of the poor bird’s head is missing now, and its plumage on one side is singed away, but its under-feathers still shine stubbornly on, awkwardly glued to a pigeon-shaped pin cushion.

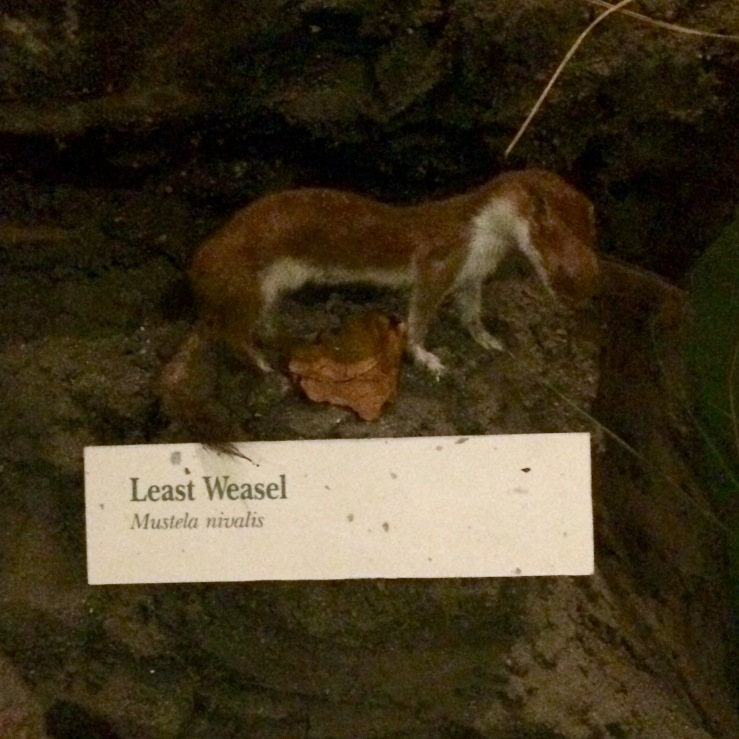

History has been a little kinder to the birds in Madeira’s natural history museum (which we visited in April); most of them still manage to look reasonably robust. But then there are the sharks:

And the cat:

I think that I love bad taxidermy because I grew up with excellent taxidermy. The Denver Museum of Nature and Science, where my mother and brother and I spent half of our summers and a good chunk of our winters, has several large halls of dioramas representing all the world’s major ecosystems, and animals so lifelike that you almost expect to see a cloud of frozen breath hovering over the Arctic wolf’s nostrils. A mountain elk still seems to gaze at you from “across a narrow abyss of non-comprehension,” as John Berger said.

As I child I once took a class about the dioramas; docents took us through the various silent habitats, pointing out particularly interesting elements and telling us a bit about how the specimens were prepared. In a classroom in the museum’s back hallways, my mother and I made a diorama of our own under the fierce supervision of a stuffed grizzly bear, reared up to his full seven- or eight-foot height.

A few years later, by chance, my father got to know the taxidermist responsible for many of these wonderful scenes. His name was Jack, and he had spent several decades traveling around the world, hunting and gathering wild flora and fauna for the museum’s collection. He was often accompanied by his wife Lila, a gorgeous opera singer who serenaded the tribes of the Kalahari during their stay in South Africa. My father took me with him to their house once. Jack was in his seventies or eighties by then, a surprisingly small, gentle man whose favorite animal was the duck.

Jack’s living room was a dizzying exhibition of his best work. Flocks of birds shot towards the ceiling lamps in formation over the head of a mountain goat perched on the mantlepiece. A bobcat reached for its prey, every muscle in its back beautifully tensed, a magpie’s long tail feather just barely brushing its outstretched paw. In one corner stood the polar bear – its massive shoulder loomed a good foot above my own head – who had once charged Jack and his friend in the far north, and whom Jack had had to shoot at point-blank range. A room like that should be astoundingly creepy, but it was beautiful. The hours upon hours of love, respect, and meticulous craft Jack had poured into his specimens were evident in their bodies – and yet they were also immediately forgotten, for the artist disappeared into his every creation, and the walls of his home instead seemed to tremble with the souls of the beasts who could, at any minute, spring once again into motion.

The last time K. and I were in Chicago, we went to the Field Museum and learned about the apparent founder of artistic taxidermy, Carl Akeley. After an early career marked by the single-minded pursuit of the perfect stuffed creature and a surprising amount of drama, Akeley had his breakthrough in the late 1880s. He developed the use of armatures and the practice of hiding the seams on the sewn hides; after a trip to Africa in 1905, he caused a sensation with his work “The Fighting African Elephants,” still on view at the Field Museum:

Around this time he also created a piece called “The Four Seasons,” which depicts a deer family not only in four different environments (complete with a supporting cast of snakes, rodents, and birds), but with their different winter and summer coats and antlers as well. “The Four Seasons” is universally referred to as “the Mona Lisa of taxidermy.”

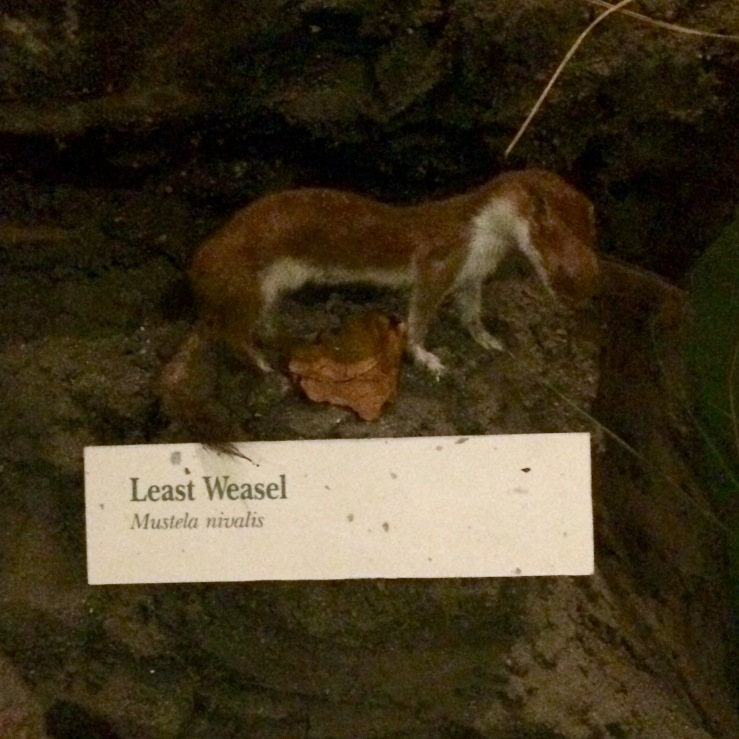

Right across from this paragon of the art, however, the Field Museum also displays a tiny, dejected relic of a less ambitious time – and Jack forgive me, but I just love it: